Multiples Arbitrage in U.S. Private Equity (2015–2025)

Inside the Most Popular PE Playbook: Roll-Ups, Repricing, and Returns

In private equity, multiple arbitrage (or multiple expansion) means buying companies at lower EBITDA valuation multiples and selling them at higher multiples. It is most commonly achieved via buy‑and‑build strategies – acquiring a platform company and then rolling up many add‑on acquisitions. The idea is that larger combined companies typically command higher price/EBITDA multiples than the smaller firms that are tucked in. In practice, a PE fund acquires a platform and then sequentially adds smaller firms (often at lower EBITDA multiples). The blended entry multiple of the combined company falls, so when it is re‑valued at a higher multiple on exit, the difference (“multiple arbitrage”) boosts returns.

As Schwetzler (2024) defines, “if the add-on transactions command lower multiples, the average entry multiple of all acquired companies is decreasing… This effect is called multiple arbitrage.”

Bain also explains that buy-and-build has long worked because “larger companies [get] higher valuations than smaller ones. This opens the door to multiple arbitrage – creating a large, high-multiple company by tucking in add-ons at lower multiples.”

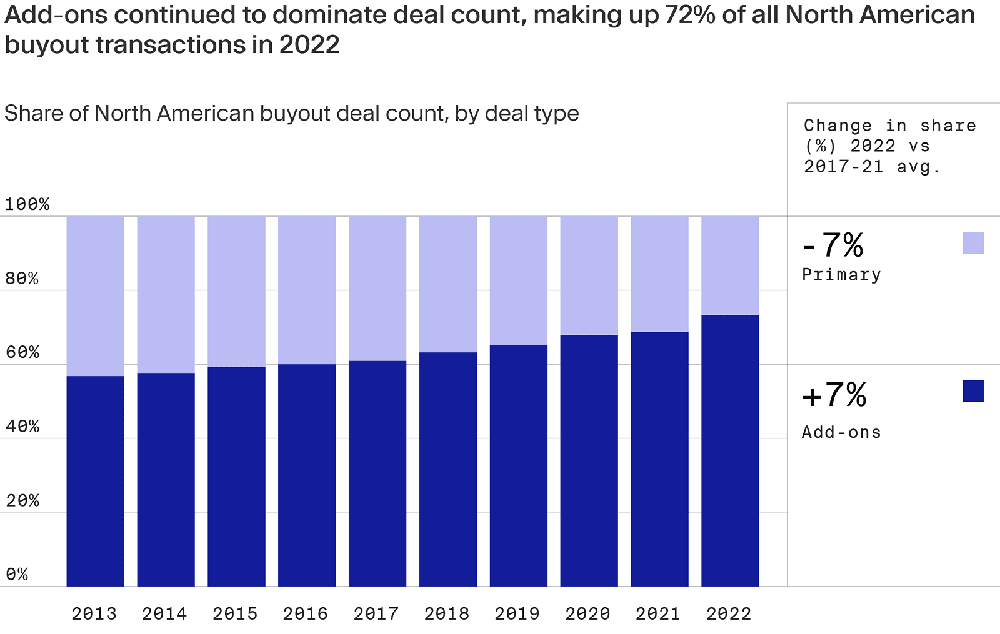

Figure: Add-on deals (dark blue) dominate U.S. buyout activity. Bain reports ~72% of North American buyouts in 2022 were add-ons, reflecting the prevalence of buy-and-build/multiple-arbitrage strategies.

Historical Examples (2015–2024)

Over the past decade, numerous U.S. buyouts have delivered gains largely via multiple arbitrage. Notable cases include:

YETI Coolers (2012–2020):

Cortec Group bought a majority of outdoor-gear maker YETI in 2012 (when YETI had ~$40M revenue) for about $67M. Over the next years Cortec helped YETI scale (adding product lines and improving operations) and prepared it for an IPO. By 2016–2020 Cortec had sold nearly all its stake on public markets. Cortec reported it “generated greater than 25× invested capital on a gross basis… and returned… more than 20× their original investment.” In effect, the exit implied an EV/EBITDA multiple many times higher than the original buy-in. This case is often cited as a prime example of extreme multiple expansion.

Berlin Packaging (2007–2014):

Investcorp bought U.S. plastics-container maker Berlin Packaging for about $410M in 2007 (roughly mid-double-digit EBITDA multiple). Investcorp and then Oak Hill built it via several add-ons. In 2014 Oak Hill sold Berlin Packaging for $1.43B – over 3× the original price. Bain notes this as a classic buy-and-build: “seven years and four strategic acquisitions later… sold out… for $1.43B, creating a better than three times return.” Presumably, a portion of this gain was due to multiple arbitrage (the enlarged company commanded a much higher multiple than the original small platform).

VetCor/VCA (2010–2019):

Cressey & Co. acquired VetCor (veterinary practice consolidator) in 2010 with 41 clinics. The veterinary industry was highly fragmented, so add-ons could be bought at mid-single-digit EBITDA multiples vs. VetCor’s platform at mid-teens multiples. Cressey, then Harvest Partners (2015) and Oak Hill (2018) kept rolling up practices; by 2019 VetCor had 300+ clinics. Although still privately held, this roll-up exemplifies multiple arbitrage: small clinics sold cheaply while the growing platform justified a much higher valuation on exit or sale to strategics.

Optiv Cybersecurity (2018–):

KKR-backed Optiv grew by adding dozens of small security firms. KKR’s strategy relied on technology-sector demand and the fact that independent cyber firms trade at lower multiples than large integrators – a classic multiple-arbitrage build. (By 2024 Optiv reported $2.25B revenue, though a full exit analysis isn’t public.)

Other roll-ups:

In sectors like software, healthcare, finance, and industrial services, many PE firms used add-ons to drive multiple expansion. For instance, Cressey’s acquisition of Vitalize Consulting (an HR/marketing tech roll-up) in 2014 and consolidation of utility technologies by firms like Blue Sea Capital each aimed for higher exit multiples via scale. In general, any platform/roll-up strategy that grows via acquisitions instead of purely organic growth is a candidate for multiple arbitrage.

These examples show how PE firms can profit before even considering EBITDA growth: by simply creating a larger entity that trades at a higher valuation relative to its smaller pieces. Academic research confirms multiple arbitrage’s importance: Heisig et al. (2022) find that in buy-and-build deals the “add-on sourcing effect” – i.e. reduction of average entry multiple by buying smaller firms – contributed roughly 8% per year to equity value CAGR. When this effect is removed, buy-and-build returns fall back in line with ordinary buyouts, underscoring that multiple arbitrage materially boosts returns.

Identifying and Sourcing Multiple‑Arbitrage Opportunities

PE firms target opportunities where multiple expansion is available. Key factors include:

Fragmented Industries:

Industries with hundreds or thousands of small players (and no dominant incumbent) are ideal. Fragmentation ensures a long “long tail” of potential add-on targets (often family‑owned or founder-led businesses in niches). Examples: specialty healthcare practices (dental, vet, eye care), professional/IT services, industrial components, financial-planning offices, software verticals, etc. Moonfare (2025) notes buy-and-build dominates U.S. deals: about 72% of buyouts by count in 2022 were add-ons. Bain similarly advises focusing on sectors with “predictable growth” and enough targets of the right size, ensuring add-ons have lower valuations than the platform.

Valuation Gaps by Deal Size:

By definition, multiple arbitrage requires a valuation gap between small and large deals. Historically, smaller buyouts trade at much lower multiples. For example, Bain/PitchBook data (2013–2018) show median EV/EBITDA multiples rising with deal size: U.S. deals under $25M averaged ~5× EBITDA, while mega‑deals over $2.5B averaged ~15–18×. In 2024 GF Data found a similar pattern: deals worth $1–10M TEV averaged only ~4.5× EBITDA, whereas $10–100M deals averaged ~6.5× (and $100–500M ~9×).

Table 1. GF Data (US middle market, 2024) – lower EBITDA multiples on smaller transactions:

Deal Size (Total Enterprise Value)Median EBITDA Multiple$1–10M4.5×$10–100M6.5×$100–500M9.0×

Deal Sourcing:

In practice, firms use relationships, industry networks and brokers to find platforms and add-ons. They may launch proprietary searches in targeted niches (e.g. calling on thousands of small service firms), or work through intermediaries. Often a platform is acquired via auction or carve‑out (e.g. a private family business or corporate spin‑off), then the sponsor’s executives or an “integration team” actively identify add-on targets (through cold calling, industry events, trade shows, and executive referrals). Because add-ons are smaller, they are frequently transacted out of a company’s current revolving credit line or with seller financing, making deals faster to execute.

Finding Valuation Dislocations:

Market cycles and sector trends can create opportunities. For instance, a downturn might compress small‑cap multiples more than large‑cap multiples, widening the arbitrage gap. Analysts note that in late 2024 a large “valuation gap” emerged between seller expectations and buyer pricing (Moonfare reported a 3.8× spread in target price multiples, the widest in years). This gap (with PE funds holding dry powder) can favor aggressive buy-and-build deals. Similarly, interest-rate spikes since 2022 have depressed earnings multiples on highly-leveraged platforms, potentially making some add-ons relatively cheaper. Firms look for mispricings – e.g. sub-scale rivals trading at single-digit EBITDA multiples due to short‑term troubles – that can be bought up cheaply and folded into a healthier platform. In short, the ideal opportunity is a growing platform in a fragmented industry where (a) add-ons are available at 2×+ turns lower EBITDA multiples, and (b) operational synergies or scale benefits will justify the elevated multiple on exit.

Current (2024–2025) Landscape and Opportunities

After a sharp slowdown in 2022–23, U.S. PE activity rebounded in 2024. Dealmakers deployed record dry powder, and add‑on acquisition still accounts for a large share of deal flow.

Key observations:

Sector Tailwinds

Technology and healthcare remain especially active. A rebound in tech is driven by SaaS and cybersecurity (40% of Q3 2024 deal value was in software). The healthcare sector saw renewed PE interest: 2024 U.S. healthcare PE deal value was up ~18% from 2023. In particular, health-tech/digital health boomed: PE/VC investment in U.S. healthcare IT rose ~50% year-over-year to $15.6B in 2024. These areas feature many small, high-growth targets (e.g., medical software, AI diagnostics, telehealth providers) that can be consolidated into larger platforms.

Fragmentation Niches

Other niche roll-up plays continue. For example, consolidation is ongoing in veterinary clinics, dental practices (e.g., Smile Brands), eye-care chains, specialty clinics, home health, behavioral health, etc. In industrials, specialized manufacturing and distribution (e.g., process equipment, MRO parts) offer fragmentation. Financial services (regional bank and fintech roll-ups) are periodic targets if valuations align. PE firms are also exploring newer arenas: climate-tech services, logistics and supply-chain software, online business services, etc.

Valuation Dynamics

With broadly higher base rates, large-platform valuations have generally compressed, but a search for yield and growth persists. Many GPs see 2024–25 as a “window” to execute buy-and-build before competition returns. Reports note that after the 2023 lull, private credit availability and renewed lender appetite have helped fund LBOs again, narrowing the valuation gap. Deal values rebounded ~19% in 2024, and add‑ons remain plentiful. In practice, sponsors may find that mid-market entry multiples (say 6–8× EBITDA) combined with organic growth/margin gains can still enable double‑digit IRRs even if exit multiples are only modestly higher. The persistent multiple spread suggests ongoing arbitrage potential at small‑deal scales. In sum, areas where small targets trade at single-digit multiples (e.g., 5–7×) and larger peers are trading at 10×+ could yield arbitrage gains, especially if earnings grow in the interim.

Execution: From Acquisition to Exit

In practice, private equity firms execute multiple-arbitrage strategies through a disciplined process:

Platform Acquisition

The fund finds a stable platform company, often with a seasoned management team and recurring cash flow. The entry price may already be at a high multiple (if it’s a strong business), but the platform’s strengths (brand, systems, cash flow) will support further acquisitions. Often the fund will use leveraged financing to boost equity returns. The platform company usually makes the add-on acquisitions – not the PE fund – so it’s critical that the company generates consistent free cash flow to finance deals in succession.

Integration & Value Creation

After closing the platform buyout, the PE firm (along with the platform’s management) aggressively pursues add-on acquisitions. These are typically smaller firms paying well below the platform multiple. Operationally, the combined company consolidates back-office functions, purchasing, and branding. Efficiencies (scale economies, centralized marketing, shared R&D) are implemented to raise margins. Management expertise is often brought in (a common PE theme is to install experienced executives who excel at integrating companies).

The objective is twofold:

Grow EBITDA organically (through cross-selling or pricing power), and

Reduce costs.

Given current conditions, sponsors must drive organic growth and margin improvement to achieve desired returns – in other words, don’t rely solely on arbitrage.

Monitoring the Arbitrage

Throughout the hold period, the sponsor tracks the blended entry multiple of the platform-plus-add-ons. As each new add-on is acquired below the current platform multiple, the average entry multiple falls. For example, if a $100M platform was bought at 10× and a $10M add-on at 5×, the pro forma $110M EBITDA platform trades at ~9.5× overall, immediately “creating” value. PE accountants may explicitly calculate a “multiple conversion” metric, and monitor the expected exit multiple under different scenarios. Academic analysis suggests this multiple-sourcing effect can add ~8% annual return.

Timing and Exit

The exit is typically timed when market conditions allow a high valuation. If buy-and-build momentum continues, the enlarged company might be sold to another financial buyer or strategic acquirer at the higher platform multiple (e.g., 12×, 15×). For example, Berlin Packaging was sold when larger industrial peers commanded far higher multiples than the original smaller units. Alternatively, a successful buy-and-build may position the company for an IPO at a strong public-market valuation.

Sponsors are advised to always prepare an exit story: if consolidation is not far enough along, the next buyer might continue the roll-up strategy, or a strategic buyer may pay a premium for a scaled-up platform.

Execution risks exist: if too many buyers chase add-ons, the arbitrage can evaporate. For instance, in the funeral-home roll‑up, once most mid-size targets were acquired, remaining companies became either very small or very large, and the multiple gap disappeared.

Thus, GPs often try to invest early in a consolidation wave. During the hold, investors also use leverage: smaller add‑ons often require minimal new equity (debt rolls under the existing facility). Middle‑market deals in 2024 sometimes had 60–70% senior debt, especially on add-ons, which amplifies returns.

Academic and Practitioner Insights

A growing body of research confirms the role of multiple arbitrage:

A 2024 study explicitly defines and models its impact.

Heisig et al. (2022) decompose buy-and-build returns and find multiple arbitrage is a material source of value.

Industry reports confirm that buy-and-build has become the most popular PE strategy in recent years due to arbitrage and synergies.

KPMG and Ropes & Gray note that firms continue achieving high IRRs by combining multiple arbitrage with operational improvements.

PitchBook data illustrates the multiple spread by deal size.

In summary, while sometimes dismissed as “financial engineering,” multiple arbitrage is a well-documented driver of PE returns. U.S. PE firms routinely plan for it through buy-and-build roll-ups, especially in fragmented sectors. Over the past decade, numerous case studies (YETI, Berlin Packaging, VetCor, etc.) show how buying small and selling big can multiply investor value.

Today, despite higher interest rates, opportunities persist where add-on targets trade well below platform multiples and can be acquired with available financing. Successful PE investors combine multiple arbitrage with genuine business improvements to create durable, scaled companies that justify higher exit valuations.